The fortress

Text by Maria Teresa Corso.

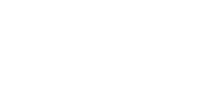

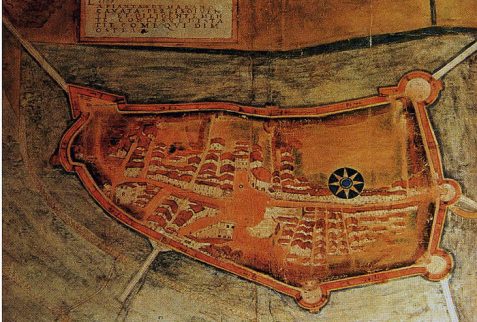

The town of Marano is situated on the site of an ancient fortress, previously a stronghold of the Patriarchy of Aquileia and then under the control of Venice for centuries. The historic town centre preserves the memory of the old urban layout, whose support structure has remained the same.

Given the importance of this place, with a perimeter of half a mile (equal to approximately 620 steps), complete with embankments and moat where the galleys would enter, this fortress and its port protected the mainland from invasions from the sea.

Venice attempted to conquer the fortress on various occasions, setting fire to it multiple times. For the community, life under the patriarchy was fairly tumultuous, but the times moved in favour of the Republic which won over the Community’s dedication and alliance in 1420, as was the case for all conquered towns and ports along the coast, in addition to Friuli.

The fortress included the following buildings:

- bastions (the St. Anthony or the Moor’s bastion, the only one still visible);

- towers (the “Cicocca” or Guardhouse);

- round or crescent-shaped ramparts or towers (St. Zuanne, St. Mark, the “Little rampart”);

- gates (“de Mar”, “de Tera”, “dell’Orro”, i.e. border);

- knights;

- dividers;

- gunpowder stores and storerooms.

During the patriarch years (XI-XV century), the Community was also present in the Parliament of Friuli. As a Community, Marano, alongside the other classes of noblemen, clergy and communities, participated in the parliament’s decisions regarding the defence of the homeland, in the case of war, or sending military troops to Friuli.

During medieval times, Marano not only spoke Friulano, but also used the laws issued by the Constitutions of the Homeland of Friuli in 1365.

It is thought that Marano’s Community Charter, whose date is uncertain, was drawn up and developed precisely on the basis of the rules provided for by the Constitutions of the Homeland.

Year after year, the Venetian Republic conquered town after town and all the land along the Adriatic coast. To avoid the violence of the Venetian army, Marano signed the famous “dedication act” in 1420, thereby becoming an ally of the Republic. When the Venetians arrived to the fortress, they sent a rector or proveditor, whose task was to govern the fortress by military means, as well as all civil and legal aspects, maintaining the rules that were already in force, i.e. those relating to the Constitutions of the Homeland of Friuli.

The proveditor was responsible for administrative and military management for 16 or 18 months. Serving under him were a vicar, who could even replace him for sentencing, and who had to know the utroque iure (both civil and canon law), a registrar, similar to a notary, who would often hold a degree in law, a knight who had control over the police and who in turn would use two officials to carry out his responsibilities, known-as “bravi” (“the good”) or “birri” (“coppers”) according to the writer Manzoni. This small ‘court’ was appointed directly by the Venetian authorities. In fact, they would send to the fortress: a governor, responsible for 50 infantrymen – some of whom were put up in private homes; two captains, each responsible for 25 infantrymen; and a chief bombardier who was responsible for the gunpowder and weapons stored in the fortress.

During the Habsburg domination (1513-1542), Marano had feudal jurisdiction over various imperial villas situated in the Veneto region: Campomolle di Teor, the administrative district of Chiarisacco, Gonars, San Gervasio, Castel Porpetto, Rivarotta in the Palazzolo dello Stella.

Statue of Pietro Bernardo Bembo (1680) on the historic Gran Guardia building, two flagpoles on 17th century stone posts and the tower with busts and epigraphs

House known as the “Guards’ Wing” or the “Guardhouse in the Square”

This was the building used to guard the square. Outside, the façade features an alcove containing a stone statue of the proveditor Pietro Bernardo Bembo, popularly known as Piero Bimbi. Inside the building, you can see the stone coat of arms of Andrea Contarini. During the XV-XVIII centuries, the building was home to the guardhouse, made up of 50 infantrymen who protected the fortress square.

“Cicocca” or coastguard service

The side of the fortress guardhouse looking out to sea housed 25 infantrymen and was situated in today’s “Porta de Mar” (“sea gate”) building.

In 1613, the Proveditor Francesco Loredan reported the following to the Venetian Senate: “two vertical posts have been put in place, one, measuring 16 feet, to the side of the Cicocha that looks out over St. Anthony’s tower, and the other, measuring 20 feet, underneath this tower, with a hundred and thirty steps between them”.

“Casa delle Ragioni” or “Loggia”

Today, the ancient loggia, or “Palazzo della Comunità” (“Community Palace”), is private property and resembles loggias in other towns such as Padua, Muggia and Udine. This building is in contact with the Tower, to the north side, and the remains of the pointed stone arches remain on the ground floor, from where you could once enter the large hall on the first floor. On the façade overlooking Via Sinodo, there were window frames, two-mullioned windows, pillars and archivolts of the large windows which would allow light to enter the hall, where Domenico Baietti from Udine painted in 1421.

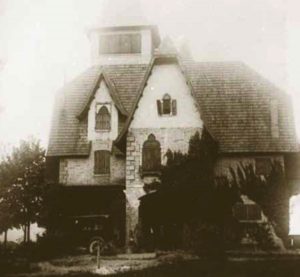

1902. Former De Asarta Villa in Marano. Note the two-mullioned windows: north-facing façade.

The two-mullioned windows used at the start of the 20th century to decorate private homes (Villa de Asarta) were most likely also used to decorate the façade of the loggia.

Local historian Tarcisio Dal Forno provides the following description of the hall inside the Palazzo della Comuntià: “You could see the ceiling supported by exposed beams, resting symmetrically, to the sides of the walls, on stone barbicans, whereas the floor is made from oak laid in a herringbone pattern. The walls are dotted with frescoes, including the emblem of the municipality consisting of a wild boar feeding on acorns underneath an oak tree. Next to this, a spread winged eagle against the background of the sea blue shield”.

All the acts of the fortress government were dealt with inside the Palazzao della Comunità. In the large hall, where the “Council of the Magnificent Community” would meet, there were wooden benches. Meetings open to the public would instead be held on the ground floor, surrounded by wrought iron gates, including the auction for the fishing valleys, the “tòco” i.e. seasonal draw to decide who would get to fish in which areas and bids for the “fontico”, i.e. the place where food products – such as oil and flour – necessary for fortress life, were managed and sold.

The historic town walls

Text by Maria Teresa Corso.

Over the last thirty years, the ancient dedication to the Serenissima, written in the Charter, is read to the Community by the first citizen on the first day of the year. This includes certain information regarding the town walls: it states how a fisherman wanted to get a new boat so was forced to go to Istria, at his own expense, to bring a load of stones back to the fortress, to be used to strengthen the walls.

There has always been some discussion about the fact that the Charter has no precise date: for some historians, it dates back to the XV century according to a linguistic analysis of the document, whereas the year 1623 mentioned in the text refers to some additional content.

There is a well-known saying in local dialect “le mure le ze nostre” (“the walls are ours”), making reference to an old song from Marano. In actual fact, the material used to build the walls was purchased from a construction entrepreneur, Mr. Carandon, the former mayor of the municipality of Muzzana del Turgnano, who also owned other plots inside the fortress.

Once the price was agreed for the purchase of the material (Istrian stone), Mr. Carandon transferred ownership of the walls to the local authorities, through a notarial act. But, for the locals, the stones in the walls ‘felt’ like their own, which is where the song from the end of the 19th century got its inspiration: “… Le mure le ze nostre e no de Carandon, sior Pimico de note, ze ‘ndò in tombolòn …”.

In 1894, the Municipality, through a series of acts and resolutions and the passing of external government commissioners, felt the need to knock down the walls, just like many other administrations across Europe were doing at the time, supported by the discovery that endemic diseases could be be fought through better ventilation.

St. Anthony’s bastion

This bastion can still be seen today along the Molino Canal: it is incorporated into the property belonging to the company Igino Mazzola Spa that turned it into a number of departments for processing tuna in brine. It got its name from St. Anthony’s church, which disappeared in the XVIII century.

The Mazzola factory has now been closed for a long time. A number of new project proposals aim at renovating the factory in order to build a residential complex, which also include the ancient artefacts, such as the remains of the two ancient churches that had been incorporated into the building – St. Anthony’s and St. Peter’s with the relative cemeteries – , a 16th century water well that was inside the park of Palazzo Zapoga, on the southern side of the factory, the stone heraldic shield of the Proveditor Pietro Memmo (1571) on the external façade of the walls and the hexagonal-based gunpowder store, built by the Proveditor Giuseppe Michiel.

St. Mark’s bastion

27th April 1561. Report by the Proveditor Marco Longo: “… Today, to fulfil my duties, I bought many boat-fulls of Massegna stone for a good amount of mortar material in order to build the foundations for St. Mark’s bastion, once and for all”.

In 1594, there was the problem of digging the soil out of the ditch where the bastion would be built, i.e. St. Mark’s crescent-shaped bastion.

In the 50s, Tarcisio Dal Forno wrote that this bastion “..was positioned where the rectory stands today, the former Villa de Asarta which included the home to the pharmacy, former home of the deceased Dr. Bianchi and neighbours…”.

In 1971, Villa de Asarta was demolished to make room for today’s nursery school building.

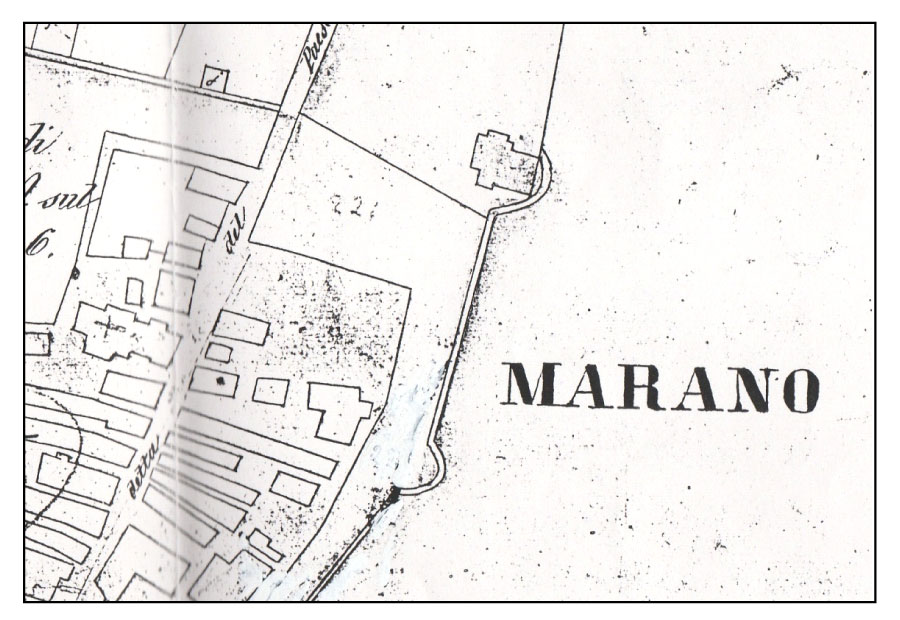

Land registry map. You can see the round bastion and Villa de Asarta built on top. In 1898, Villa de Asarta was built on St. Mark’s Bastion, the foundations of which can be seen. You can also see the two-mullioned windows that belonged to the 16th century public loggia.

St. John’s bastion

This rounded bastion stood to the north of the town, underneath the foundations of today’s Z.G. house. Together with St. Mark’s bastion, this overlooked the small fort of Maranuzzo, notoriously owned by the archdukes, who had to be strongly resisted and carefully watched over.

This bastion got its name from the nearby “St. John of the Beaten” church.

The “little rampart”

This building stood between St. Mark’s bastion and St. Anthony’s bastion. Its role was to defend the side of the wall that overlooked St. Peter’s island, the place that was disputed by the Archdukes for a number of decades, i.e. by the nearby town of Carlino.