Text by Maria Teresa Corso.

On the corner of the tower, there’s still an artefact dating back to the XVI century: a surviving link of a thick chain, used to tie up those who had committed crimes in order to subject them to the public ridicule of passers-by.

On the upper section of the tower, there is the working clock with its impressive frame. This clock’s mechanism dates back to the 18th century (1739) and has been telling the time for the town’s residents ever since, although it does have to be wound up by hand every day, with the person in charge having to climb 98 steps in order to reach the compartment where it is kept. Mrs. Angelina Milocco, who lived to the age of 108, told of how the clock used to have a huge glass face, which you could see from the lagoon, but it was struck by lightning and never restored. Recently, the ancient mechanism broke down, so the local council replaced it and integrated a more modern and functional system.

On the tower’s south façade, there are half busts of Proveditors belonging to the Bragadeno, Gradenigo and Foscarini families, positioned inside alcoves.

Some plaques are circled by friezes with symbols from the Renaissance period, from war trophies to armour to the community’s coat of arms in stone.

In 1557, the Proveditor Gerolamo Contarini, whose coat of arms can be seen in the architrave of the tower’s access door, had two prisons built which can still be seen today. One was underground and one was above ground, with the latter becoming a storeroom for weapons and gunpowder in 1601 “…if there was a prisoner with desperate thoughts, he could commit a significant crime here, causing great damage to those inhabitants…”.

Do the two sculpted figures under the tower represent a bishop or St. Anthony?

On the tower’s eastern façade, in an alcove, there is the “Lion” known as “in moleca” (“in a soft crab position”): given its crouched position, the Venetians say that it represents a ‘crab’ that becomes soft by shedding its shell, becoming a “moleca” (‘soft crab’ in dialect). The Venetian lion is generally represented very majestically with a sword and the Gospel, standing on four paws. In other representations, it is seen in the “moleca” (“soft crab”) position. These names refer to the lion’s posture: “rampant”, i.e. seen to the side on his hind legs; in the “moleca” position, meaning he is seen front on, sitting down with his wings spread; passing by, meaning he is seen from the side with his front right paw resting on the book. If the lion is accompanied by the book (the Gospel) open, this means that the town in which it was located had to pay taxes; if the lion’s paw is resting on a closed book, with the sword pointing towards the book or pointing upwards, then the town was exempt from paying taxes, for war-related merits.

On the tower’s western façade, there is the plaque of Proveditor Tron (1608), who went on to become doge, with his sculpted coat of arms.

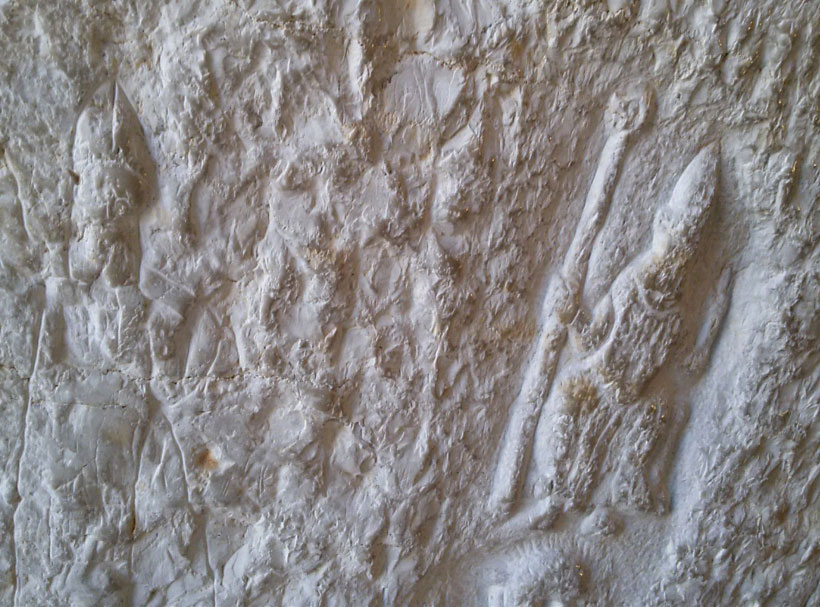

There is also a bas-relief showing typical elements of a military fort, such as the drum, surrounded by ribbons, that are probably muskets (the upper part of the frieze is missing), a gunpowder barrel and a piece of artillery. There is perhaps a “mascolo” above the cannon, i.e. the equipment used to load the weapon, a “cazza” to insert the gunpowder and a number of balls or bullets.

In the squares in front of the tower, one called Vittorio Emanuele II (formerly Piazza Grande) and the other “Piazza Marii”, there are two well curbs for the collection of water, made from Istrian stone. These hexagonal structures date back to the XVI century, with one depicting the generous builder Bernardo Contarini, and the other Tiepolo.

During the XII century, Marano was a parish, under the chapter of Aquileia, which imposed its own parish priest. This made Marano a “villa” to all intents and purposes, under patriarchal jurisdiction, sharing traditions and festivities on the set days, imposing the collection of the tithes throughout the area of Friuli and therefore imposing also the language, as can be seen in the list of registered taxpayers, at least two thirds of which had Friulian names.

Today, we only speak of Marano dialect, which is similar to the one spoken in Grado and the south of the Veneto region.